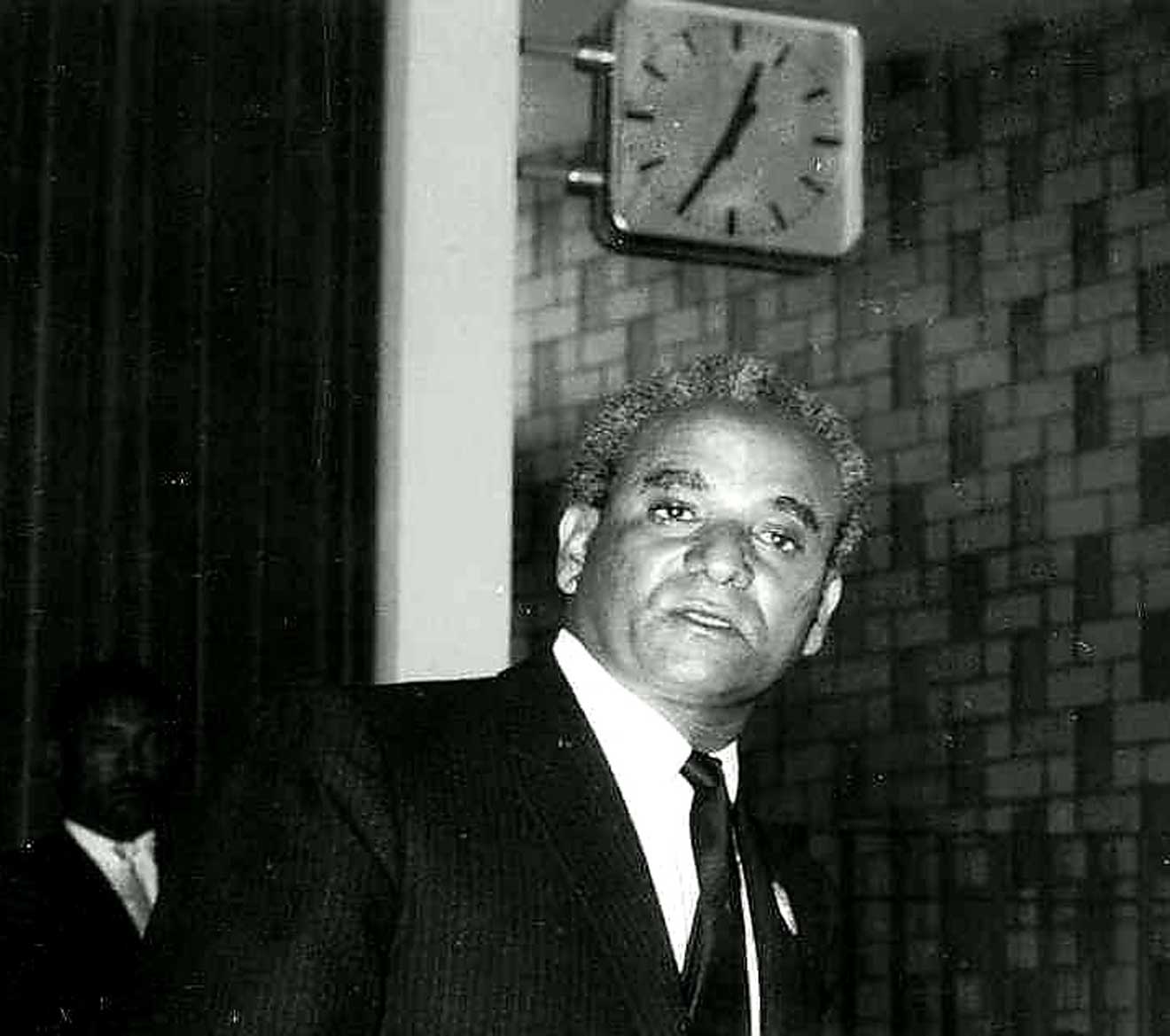

klilu Habte-Wold was the son of a rural Ethiopian Orthodox priest from the Bulga district of Shewa province. He and his brothers, Makonnen Habte-Wold and Akalework Habte-Wold benefited from the patronage of Emperor Haile Selassie, who had them educated. Aklilu Habte-Wold attended the French lycee in Alexandria, then afterwards studied in France.

Upon returning to Ethiopia, Aklilu became the protégé of the powerful Tsehafi Taezaz (“Minister of the Pen”) Wolde Giyorgis Wolde Yohannes, another man of humble birth, who had become a powerful figure in Ethiopian government, and a close advisor to the Emperor, with his appointment as Tsehafi Taezaz.

Wolde Giyorgis recommended the sons of Habte-Wold to the Emperor, who promoted them through the ranks so that the two eldest, Makonnen and Aklilu, became particularly influential with the monarch. Their humble origins, and the fact that they owed their education and advancement solely to the Emperor, allowed Emperor Haile Selassie to trust them implicitly and to favor them and other commoners of humble origin in government appointments and high positions at the expense of the aristocracy, whose loyalty to his person, rather than to the institution of Emperor he suspected. The Emperor’s preference for such men as Aklilu Habte-Wold over the high nobles created resentment among the aristocracy, who believed they were being displaced by these new western educated “technocrats”.

ollowing the fall from favor of Tsehafi Taezaz Wolde Giyorgis in 1958, the Emperor appointed Aklilu to replace him as Tsehafi Taezaz. In April 1961, four months after the previous Prime Minister Abebe Aragai had been killed in a failed coup, the Emperor promoted Aklilu Habte-Wold to that office, while retaining the powerful office of Tsehafi Taezaz in his portfolio. These two posts gave Aklilu a level of confidence with the Emperor that no one outside of the Imperial Family shared.

This appointment, and the following increase of commoner “technocrats” in positions of power and influence greatly disturbed the more conservative elements in the Imperial Family, the aristocracy, and the Ethiopian Church. Two camps evolved at court, with Prime Minister Aklilu and his fellow non-noble “technocrats” on one side, who dominated the various ministries and the Imperial Cabinet, against the nobility who were represented by the Crown Council, and led by Ras Asrate Medhin Kassa.

hen student protests, military mutinies and an economic downturn caused by the oil embargo erupted in 1973 into a popular uprising against the government, calls went out for Prime Minister Aklilu to be dismissed. On 23 February, then the next day, the Emperor made a number of concessions to the various groups of protesters.

Meanwhile, Aklilu had grown frustrated and weary of holding a position with much responsibility but no authority. John Spencer offers one example, only a few months prior to this crisis, of Aklilu’s loss of power:

In foreign affairs where, for decades, his views were uncontested, he was now confronted by Minister of Foreign Affairs Minassie Haile, who did not share his views on foreign policy. For Minassie, it was sufficient to go to His Majesty to obtain a compliant authorization of an opposite line of action. A case in point … was whether or not the Emperor should make an urgent visit to Riyadh to consult with King Faisal. Ill-advisedly, Aklilou accepted a show-down in front of His Majesty. Aklilou lost. Without a constituency, with only a vacillating monarch to turn to, Aklilou expressed to me his concern for the future.